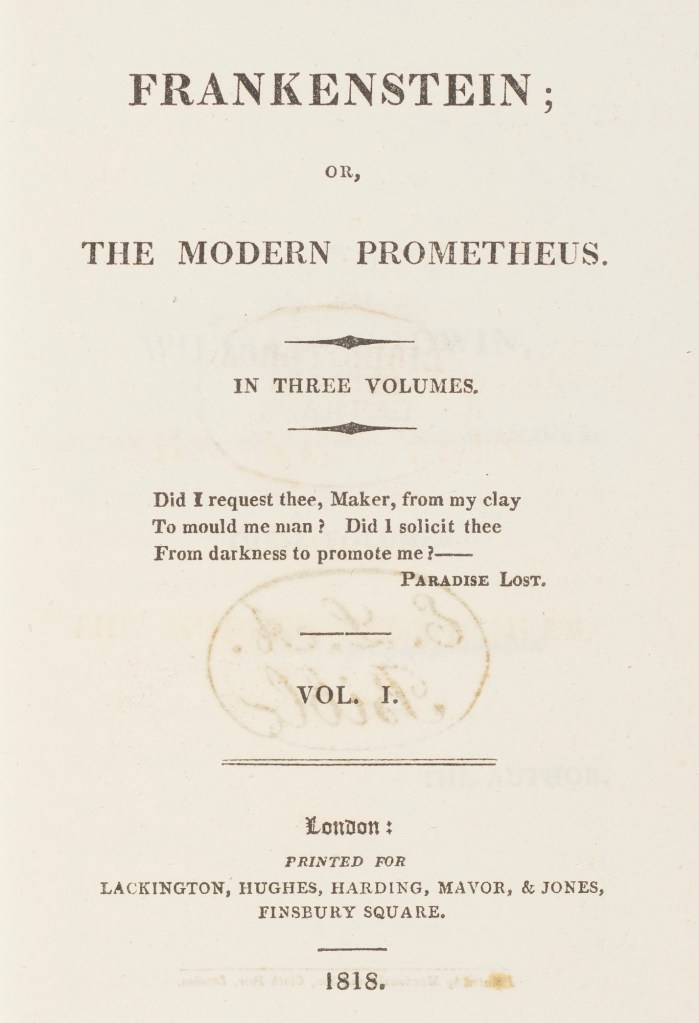

When Mary Shelley chose to inscribe a quotation from John Milton’s Paradise Lost on the title page of her 1818 novel Frankenstein, she was not only drawing attention to her literary influences but also aligning her work with one of the most significant texts of the English canon. The line, spoken by Adam, lamenting his creation and fall, frames Shelley’s story as a modern retelling of Milton’s epic, with Victor Frankenstein cast as a flawed creator and the Creature as both Adam and Satan. To understand why Shelley made this choice, we must look at Milton’s place in 17th and 18th century culture, the Romantics’ reception of Paradise Lost, and the way the epic resonates throughout Frankenstein.

Milton, the Man

John Milton (1608–1674) was one of the most important voices of the English seventeenth century. A poet, political writer, and staunch advocate of republican liberty, Milton engaged with the theological and political debates of the English Civil War, serving in Oliver Cromwell’s government as Latin Secretary. His poetry reflected not only immense erudition but also a profound engagement with questions of free will, divine justice, and the relationship between humans and God. By the end of the century, Milton’s reputation as England’s great epic poet rivaled that of Homer and Virgil, and his work was revered as both a literary and theological authority.

Paradise Lost and the Romantics

For the Romantic poets of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Paradise Lost was not only a model of sublime poetic achievement but also a text that captured their fascination with rebellion, imagination, and the limits of human power. The Romantics were particularly struck by Milton’s portrayal of Satan, whose defiance and rhetorical brilliance made him an unexpectedly compelling figure. Writers such as William Blake famously declared that Milton was “of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” To the Romantics, Paradise Lost dramatized the tension between aspiration and downfall, freedom and constraint; themes central to their age of revolution, industrial change, and philosophical upheaval.

But Paradise Lost excited different and far deeper emotions. I read it, as I had read the other volumes which had fallen into my hands, as a true history. It moved every feeling of wonder and awe that the picture of an omnipotent God warring with his creatures was capable of exciting. I often referred the several situations, as their similarity struck me, to my own. Like Adam, I was apparently united by no link to any other being in existence; but his state was far different from mine in every other respect. He had come forth from the hands of God a perfect creature, happy and prosperous, guarded by the especial care of his Creator; he was allowed to converse with and acquire knowledge from beings of a superior nature, but I was wretched, helpless, and alone. Many times I considered Satan as the fitter emblem of my condition, for often, like him, when I viewed the bliss of my protectors, the bitter gall of envy rose within me.

-Chapter 15, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus

Shelley’s Frankenstein echoes Paradise Lost on nearly every level. The Creature reads Milton’s epic and comes to identify with both Adam and Satan: Adam in his sense of abandonment by his creator, and Satan in his jealousy and alienation from human society. Victor Frankenstein, meanwhile, occupies a quasi-divine role but lacks God’s benevolence and foresight, becoming instead a failed maker whose negligence leads to ruin. By framing her novel with Milton’s verse, Shelley makes it clear that her tale is not just a gothic horror story but a meditation on creation, responsibility, and the tragic consequences of human ambition.

A Very Brief Synopsis of Paradise Lost

- Book I: Satan and the rebel angels, cast into Hell, gather and resolve to continue their war against God through cunning rather than force.

- Book II: In Pandemonium, Satan volunteers to journey to the new world of Man while his followers debate strategy.

- Book III: God foresees the fall of humanity; the Son offers himself as redeemer. Satan begins his journey toward Earth.

- Book IV: Satan enters Eden and, disguised, observes Adam and Eve, envying their innocence.

- Book V: The angel Raphael visits Adam, warning him of Satan’s rebellion and stressing obedience.

- Book VI: Raphael recounts the war in Heaven, in which the Son ultimately defeats Satan and casts out the rebels.

- Book VII: Raphael describes the creation of the world, affirming divine order.

- Book VIII: Adam questions Raphael about the cosmos and recounts his own first experiences of consciousness and meeting Eve.

- Book IX: Satan, in the form of a serpent, tempts Eve to eat from the Tree of Knowledge; she persuades Adam to join her, and both fall.

- Book X: Sin and Death cross into the world; God pronounces judgment on Adam, Eve, and Satan. (The quote Shelley used on the cover page can be found here.)

- Book XI: The angel Michael reveals to Adam future human suffering, including Cain and Abel.

- Book XII: Michael concludes his prophecy with visions of redemption through Christ; Adam and Eve, comforted by hope, leave Eden hand in hand.

Why should I care?

Mary Shelley’s invocation of Milton’s Paradise Lost was not incidental but deliberate: it situates Frankenstein within a literary and philosophical tradition that grapples with creation, rebellion, and loss. For Shelley’s contemporaries, Milton represented both the height of poetic achievement and a source of radical, even unsettling, ideas. By weaving Milton into her narrative, Shelley ensured that her “modern Prometheus” would not only haunt Gothic literature but also speak directly to the Romantic struggle with ambition, alienation, and the costs of human freedom.

O miserable of happy! Is this the end

Of this new glorious world, and me so late

The glory of that glory, who now become

Accursed, of blessed? hide me from the face

Of God, whom to behold was then my highth

Of happiness!—Yet well, if here would end

The misery; I deserved it, and would bear

My own deservings; but this will not serve:

All that I eat or drink, or shall beget,

Is propagated curse. O voice, once heard

Delightfully, Encrease and multiply;

Now death to hear! for what can I encrease,

Or multiply, but curses on my head?

Who of all ages to succeed, but, feeling

The evil on him brought by me, will curse

My head? Ill fare our ancestor impure,

For this we may thank Adam! but his thanks

Shall be the execration: so, besides

Mine own that bide upon me, all from me

Shall with a fierce reflux on me rebound;

On me, as on their natural center, light

Heavy, though in their place. O fleeting joys

Of Paradise, dear bought with lasting woes!

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould me Man? did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me, or here place

In this delicious garden? As my will

Concurred not to my being, it were but right

And equal to reduce me to my dust;

Desirous to resign and render back

All I received; unable to perform

Thy terms too hard, by which I was to hold

The good I sought not. To the loss of that,

Sufficient penalty, why hast thou added

The sense of endless woes? Inexplicable

Thy justice seems; yet to say truth, too late

I thus contest; then should have been refused

Those terms whatever, when they were proposed:

Thou didst accept them; wilt thou enjoy the good,

Then cavil the conditions? And, though God

Made thee without thy leave, what if thy son

Prove disobedient, and reproved, retort,

“Wherefore didst thou beget me? I sought it not!”

Wouldst thou admit for his contempt of thee

That proud excuse? yet him not thy election,

But natural necessity begot.

God made thee of choice his own, and of his own

To serve him; thy reward was of his grace;

Thy punishment then, justly is at his will.

Be it so, for I submit; his doom is fair,

That dust I am, and shall to dust return.

O welcome hour whenever! Why delays

His hand to execute what his decree

Fixed on this day? Why do I overlive,

Why am I mocked with death, and lengthened out

To deathless pain? How gladly would I meet

Mortality my sentence, and be earth

Insensible! How glad would lay me down

As in my mother’s lap! There I should rest,

And sleep secure; his dreadful voice no more

Would thunder in my ears; no fear of worse

To me, and to my offspring, would torment me

With cruel expectation. Yet one doubt

Pursues me still, lest all I cannot die;

Lest that pure breath of life, the spirit of Man

Which God inspired, cannot together perish

With this corporeal clod; then, in the grave,

Or in some other dismal place, who knows

But I shall die a living death? O thought

Horrid, if true! Yet why? It was but breath

Of life that sinned; what dies but what had life

And sin? The body properly had neither,

All of me then shall die: let this appease

The doubt, since human reach no further knows.

For though the Lord of all be infinite,

Is his wrath also? Be it, Man is not so,

But mortal doomed. How can he exercise

Wrath without end on Man, whom death must end?

Can he make deathless death? That were to make

Strange contradiction, which to God himself

Impossible is held; as argument

Of weakness, not of power. Will he draw out,

For anger’s sake, finite to infinite,

In punished Man, to satisfy his rigour,

Satisfied never? That were to extend

His sentence beyond dust and Nature’s law;

By which all causes else, according still

To the reception of their matter, act;

Not to the extent of their own sphere. But say

That death be not one stroke, as I supposed,

Bereaving sense, but endless misery

From this day onward; which I feel begun

Both in me, and without me; and so last

To perpetuity;—Ay me! that fear

Comes thundering back with dreadful revolution

On my defenceless head; both Death and I

Am found eternal, and incorporate both;

Nor I on my part single; in me all

Posterity stands cursed: Fair patrimony

That I must leave ye, Sons! O, were I able

To waste it all myself, and leave ye none!

So disinherited, how would you bless

Me, now your curse! Ah, why should all mankind,

For one man’s fault, thus guiltless be condemned,

It guiltless? But from me what can proceed,

But all corrupt; both mind and will depraved

Not to do only, but to will the same

With me? How can they then acquitted stand

In sight of God? Him, after all disputes,

Forced I absolve: all my evasions vain,

And reasonings, though through mazes, lead me still

But to my own conviction: first and last

On me, me only, as the source and spring

Of all corruption, all the blame lights due;

So might the wrath! Fond wish! couldst thou support

That burden, heavier than the earth to bear;

Than all the world much heavier, though divided

With that bad Woman? Thus, what thou desirest,

And what thou fearest, alike destroys all hope

Of refuge, and concludes thee miserable

Beyond all past example and future;

To Satan only like both crime and doom.

O Conscience! into what abyss of fears

And horrours hast thou driven me; out of which

I find no way, from deep to deeper plunged!-Excerpt from Book Ten of Paradise Lost

Leave a comment